Get the weekly SPARTANAT newsletter.

Your bonus: the free E-Book from SPARTANAT.

TRAINING: Austrians in Africa

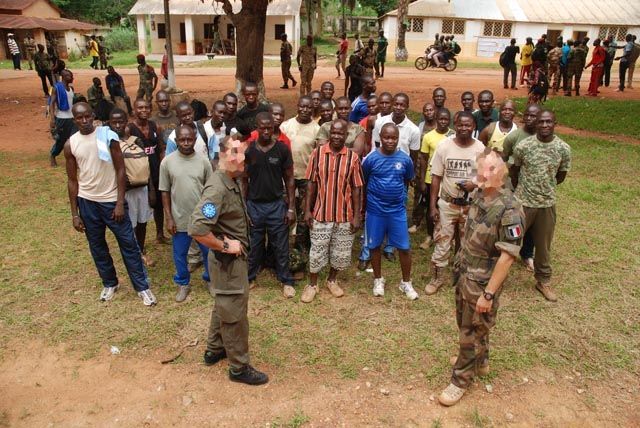

The text describes the dire state of the Central African Armed Forces, highlighting the lack of equipment, organization, and structure. The arms embargo imposed on the country has left the army defenseless, facing well-equipped militias. Despite efforts to rebuild the army, it remains incapable of fulfilling its duties, relying on French and UN troops for support. The text questions the feasibility of establishing a professional army in the unstable region, hinting at a gradual lifting of the arms embargo to allow for progress.

It is a pitiful sight that can be seen in Camp Kassai - the only usable barracks of the FACA (Central African Armed Forces). In one corner, half a dozen rifles lean: four rusty carbines, a pump-action shotgun, and an undefinable, apparently self-assembled object, all of which do not look like they could fire a single shot. Magazines are haphazardly fixed with duct tape, and frayed plastic strings serve as slings.

Anyone who believes they are in front of a camp for retired equipment is mistaken: these are the only weapons available to the best infantry battalion of the FACA. Not only does it have practically no rifles and pistols, it also has no vehicles, armored or unarmored - let alone aircraft. In the barracks, just a few wrecks are decaying: old Russian troop carriers, a gutted helicopter, a broken cannon.

The army of the Central African Republic, a country the size of Ukraine, is more or less defenseless. This is due to a somewhat bizarre arms embargo imposed by the international community after civil-war-like conditions broke out three years ago.

The army of the Central African Republic, a country the size of Ukraine, is more or less defenseless. This is due to a somewhat bizarre arms embargo imposed by the international community after civil-war-like conditions broke out three years ago.

At that time, a rebel army composed of several militias, called the Séléka (Coalition), advanced on the capital Bangui. The fact that the fighters were predominantly Muslims was less due to religious reasons than political ones: Their home, the northeast of the country, had been completely neglected by the governments in the past decades - a phenomenon that is often observed in Africa and leads to uprisings or coups. The Séléka were opposed by the Christian Anti-Balaka.

What followed was a massacre with thousands of dead and a multinational intervention by French units as part of Operation Sangaris and UN troops of the MINUSCA. They were able to contain the crisis, but not completely end it. In the years since 2013, armed conflicts have claimed numerous lives, including among the international peacekeeping troops. The government changed twice, the recently elected president has just formed a new one again. Overall, the situation in the country is extremely unstable.

In addition, there are sanctions that prohibit the "sale or export of arms and other military equipment ... to the Central African Republic" and the "provision of technical assistance and intermediary services as well as the provision of financial assistance related to arms and the provision of armed mercenaries."

In addition, there are sanctions that prohibit the "sale or export of arms and other military equipment ... to the Central African Republic" and the "provision of technical assistance and intermediary services as well as the provision of financial assistance related to arms and the provision of armed mercenaries."

The absurdity of this is: the embargo affects the FACA - but of course not the militias. During the crisis, the armed forces more or less dissolved: deserting soldiers who switched sides took the bulk of the equipment. Currently, the armed forces have around 7,000 men, of whom, according to an insider's estimate, only around 4,000 are somewhat operational.

They are faced with tens of thousands (no one really knows how many) members of the Séléka and Anti-Balaka, who occupy most of the former FACA barracks. They were supposed to disarm as part of a DDR process (Disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration), but so far, only a few have complied. Whoever their leaders and backers are: they keep open the option of combating political disenfranchisement with the distribution of power, influence, and positions through violence.

They are faced with tens of thousands (no one really knows how many) members of the Séléka and Anti-Balaka, who occupy most of the former FACA barracks. They were supposed to disarm as part of a DDR process (Disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration), but so far, only a few have complied. Whoever their leaders and backers are: they keep open the option of combating political disenfranchisement with the distribution of power, influence, and positions through violence.

But the FACA not only have problems with equipment. They also lack structure and organization. The soldiers are not fed and cannot stay overnight in the barracks - which, by the way, have no security fencing, walls, or barriers. This makes them easy prey on the way to and from home. In recent years, their pay has also been irregularly disbursed. The chain of command had collapsed, corruption was ubiquitous. Meanwhile, an EU military mission, the EUMAM RCA (EU military advisory mission in the Central African Republic), has made some progress in giving the FACA at least a basic organizational structure again: but only in non-operational areas. The EUMAM mission is ending soon, but will be replaced by the follow-up mission EUTM (EU military training mission), which is also supposed to provide tactical training to the army. So far, the FACA can only be used for subordinate tasks. Anything beyond simple guard duties must be taken over by French troops or UN units.

It would be desirable for the Central African Republic to have a professional army that can actually protect the state, democracy, and the country's legitimate institutions. How much of that can realistically be achieved is questionable.

It would be desirable for the Central African Republic to have a professional army that can actually protect the state, democracy, and the country's legitimate institutions. How much of that can realistically be achieved is questionable.

However, it is heard from UN circles that the arms embargo is also intended to be gradually lifted. Then the members of the FACA could begin to consider what it would actually be like to be an army.

AUSTRIAN ARMED FORCES on the Internet: www.bundesheer.at

SPARTANAT is the online magazine for Military News, Tactical Life, Gear & Reviews.

Send us your news: [email protected]

Ad

similar

Get the weekly SPARTANAT newsletter.

Your bonus: the free E-Book from SPARTANAT.