Get the weekly SPARTANAT newsletter.

Your bonus: the free E-Book from SPARTANAT.

TERRORISM (6): For home and wife in jihad

The text delves into the journey of an Austrian teenager who joined ISIS, the factors that contribute to radicalization, and the challenges of deradicalization. It explores the link between criminality and terrorism, highlighting the complexities of extremist ideologies.

An Austrian IS sympathizer on the path to radicalization. And back. But whether it can work is by no means certain, reports an ADDENDUM investigation (as of 2017). Oliver N. is one of 307 Austrians who have gone to jihad. How do European teenagers become Islamists? And how should countries like Austria deal with radical returnees?

"It was just cool to take photos with all kinds of weapons," Oliver N. told the Austrian intelligence service after his adventurous return from the battlefields in Syria and Iraq. On the other hand, he also explained that he went to the war zones because he dreamed of a little house with a wife and child in the countryside.

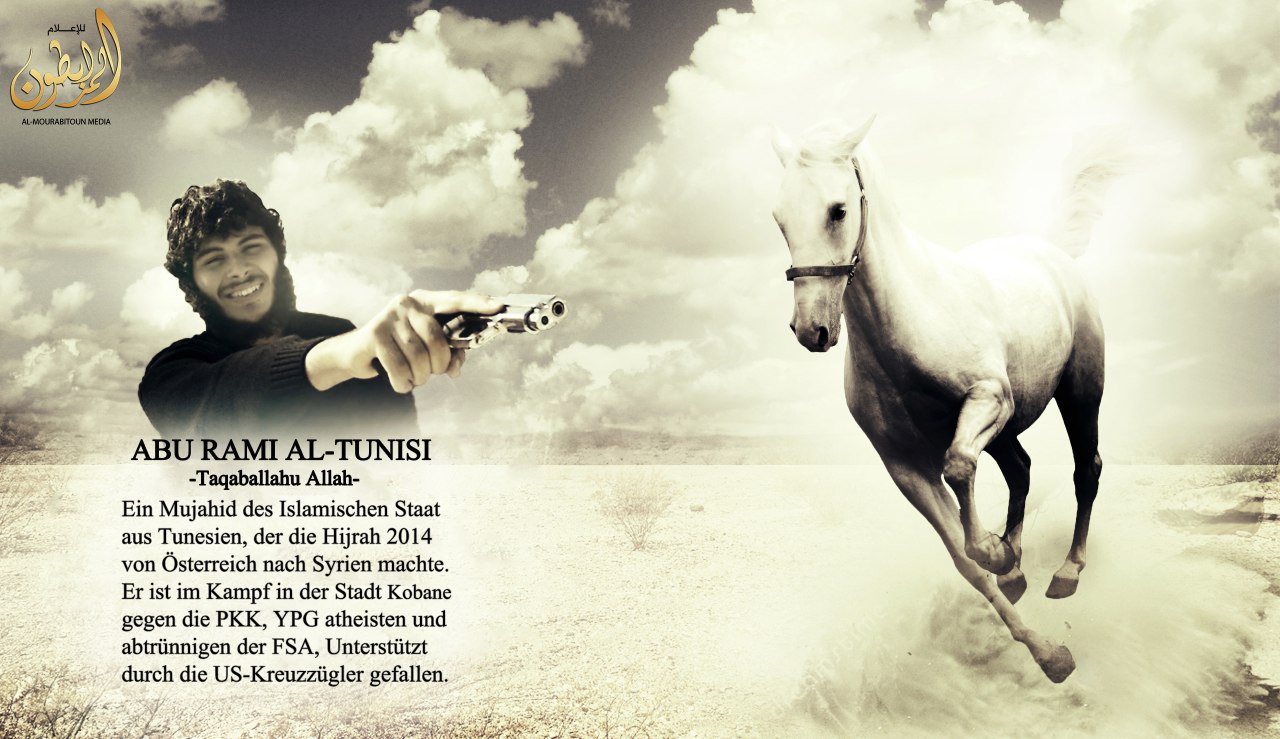

The 19-year-old teenager, now, had traveled from Vienna to the battlefields of the so-called "Islamic State" (IS) in late summer 2014, had undergone a crash course in religion there, then - according to his own account - had evacuated wounded jihadists from the battlefield as a paramedic during the battle for Kobane, had met the now deceased Austrian jihadist Firas Houidi in Raqqa (see photo above: Firas with a gun, Oliver covered by the weapon) and was then critically injured by a bomb in the same place.

This - and the sight of the torn bodies of his fellow IS fighters - likely prompted him to return to Austria. Here, he was subsequently sentenced to two and a half years in prison. Oliver N. - who has since been released from prison - could not be proven to have actively participated in combat. How could he?

But how do children, teenagers like N., or even adults become Islamist terrorists? What role does religion, specifically Islam, play in this? And: Is it "curable"?

From Criminal to Terrorist

The unsatisfactory answer for many seems to lead to a "It can't be clearly said." Looking at the biographies of people drawn from Europe to jihad, one encounters the most diverse backgrounds; not only strict religiously shaped ones, like that of Salafist preacher Mirsad O., who was sentenced to 20 years in prison last year.

After the terrorist attacks in Paris (November 13, 2015; 130 dead) and Brussels (March 22, 2016; 35 dead), it became increasingly clear: A whole series of attackers were moderately to not at all religious before their radicalization, but had a criminal background.

Salah Abdeslam, for example. He is said to have brought the attackers to the Stade de France in Paris and rented the vehicle found by investigators in front of the Bataclan music club (89 dead). He is currently in French custody.

Before his transformation into a terrorist, he was said to have been a small-time criminal in the drug scene.

Several of the Brussels attackers also have (petty) criminal pasts. Among them are robbers, car thieves, and drug dealers.

Criminality as an entry point?

In Austria, when evaluating the biographies of terrorists and foreign fighters, they go a step further. "In the area of extremism, there is a very clear link between organized crime and terrorism," concludes former director general for public security Konrad Kogler from the findings of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution and Counterterrorism (BVT). Kogler has been the police director in Lower Austria since early September.

The phenomenon is not only observed abroad, but also in a number of jihadists arrested in Austria. The range extends from simple shoplifters to arms dealers. "Frequently," said Kogler, with reference to the current State Security report published in mid-June, "chance plays a role in whether these people stay in organized crime or petty crime or radicalize and slip into the terrorist scene."

One particularly well-known "faller" is former German gangster rapper Denis Cuspert. He remains one of the most prominent representatives of European IS foreign fighters to this day. Born into difficult family circumstances, he drifted into crime. Robberies, violent crimes, prison stays, and the relative lack of success as a musician apparently drove him into an identity crisis, in which religion provided him stability. After a car accident with partial amnesia, he eventually made contact with the Salafist scene, and his radicalization took its course.

The process of radicalization leading to an attack is a matter of debate among experts. There are several theories. Former White House security adviser and current author and extremism researcher Quintan Wiktorowicz developed an approach that assumes a linear process that leads step by step to violent acts, and that these steps must be taken one after the other. Building on each other, step by step.

From Seconds to Jihadist?

Psychiatrist, terrorism researcher, and former CIA officer Marc Sageman, however, believes that radicalization is not a linear process. According to him, several factors, such as the self-perception of Islam as a victim of the West, allegedly engaged in a war against this religion, simultaneously influence the individual. Therefore, family members or authorities cannot determine how advanced the radicalization of a vulnerable person actually is.

In an interview, Sageman says that this "natural process" can sometimes take seconds, sometimes months, and often enough never reach an end.

Against this background, it becomes clear in the case of Oliver N. that converting to Islam alone is not equivalent to radicalization. The then 16-year-old Austrian jihadist precisely told the Austrian anti-terror investigation that his decision to actually go to Syria into the war zones matured only in the last two to three weeks before departure, comparatively spontaneously and in secret.

It is probably on the basis of this story that the Director of the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution and Counterterrorism, Peter Gridling, states that radicalization processes sometimes accelerate to the point where even the authorities, let alone the direct social environment of those affected, do not recognize what is happening.

Conversion in Rathauspark

But radicalization is always a very personal and individual story. Just like that of Oliver N. In his descriptions to the intelligence agency, he cited motives for his support of the IS that appear naive, banal, bourgeois, and conservative in the face of the atrocities associated with the terrorist organization. "In Vienna, I was told that I could live there in Syria and Iraq without fighting. I understood that to mean that I have a house, a wife, and get money. Here I was promised that I could choose whether to fight or not." Because it didn't quite work out as planned, he later claimed to have been misled in his recruitment.

So, a Roman Catholic baptized teenager from difficult family backgrounds, who had lived in homes since the age of five, dreamed of things that many of his peers with classic bourgeois parents also wish for. But for Oliver N., the means to achieve his desired goal were not the traditional bourgeois virtues of diligence, work, and discipline, but rather converting to Islam.

He claimed he had not been particularly religious before: "I led the normal life of a teenager, including girls, alcohol, and parties." Although he was "interested" in Islam, he was never truly a serious religious Muslim. This is also reflected in his unassuming conversion, which took place in a kind of rapid process in May 2014 not in a mosque but in Rathauspark in Vienna. The ceremony was accompanied and witnessed by four young men, some of whom appeared in hoodies. According to his own account, N. only initially informed himself through the internet about the contents and rituals of the world religion to which he now belonged.

The Path Back

Although some former and supposedly reformed jihadists like Oliver N. claim that they went to Syria not to defend the religion but for the prospect of a carefree life, skepticism is warranted. During the lives of these jihadists in Syria, there are often statements documented that do indicate ideological motives and an extremist interpretation of Islam.

When Oliver N. didn't have to face the questions of the intelligence service in the harsh light of the interrogation rooms, but was in freedom and posing with firearms above the rooftops in Raqqa in bright sunshine, his motives sounded very different. Under the war name Abu Muktail Al Almani, he broadcasted his views into the digital world on social networks: "In sha Allah apart from that I am in jihad in order to fight not to marry." (sic!)

Responding to a post in which he was asked by a third party for his opinion on the religious minority of the Yazidis, he replied, "but the knife cheered me hahaha and yes, these devil worshipers, inshallah they will be exterminated." (sic!)

Severely injured and in custody, he justified the entries by suggesting they might have come from a German jihadist with the fight name Abu Usama who had access to his account.

While the path into the radical world of jihadists is often very short and direct, the path back to normalcy can be difficult and lengthy. The process is called deradicalization and is considered the preferred method in many European countries to either act preventively as a state, or to defuse problematic cases afterwards. Oliver N. also had to undergo a program imposed by the court. Whether, and if so, how these programs work is now increasingly being critically discussed. The measures here in Austria are still comparatively undisputed.

Criticism of Deradicalization

In France, however, Senators Esther Benbassa (Green) and Catherine Troendlé (conservative UMP) published an extremely critical report in the spring of 2017. Special prisons for returning jihadists, supervised shared accommodations for radicals, and accompanying social work for vulnerable individuals do not work. Rather, due to the millions of euros in state funding, a veritable deradicalization business has developed, where associations that have no idea about the topic are active.

Or, as it is said in the industry, only hold their clients' hands and attribute the dark parts of their life story to a difficult childhood or even mental illness. However, terrorism researcher Marc Sageman says this is wrong. According to him, mental illnesses or difficult life stories are not the reasons for these careers. It is the political issues that need to be addressed with them. But some European states have not yet understood that.

But what should be done with individuals who want to leave their extremist environment on their own but cannot do it alone for various reasons? Experience has been gained with so-called exit programs abroad. On this basis, a similar project is now set to start in Austria.

For a year now, preliminary work has been underway at the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution and Counterterrorism (BVT). The state security service, however, sees itself only as a driver for the project, which is currently in the initial phase. Others will implement it directly, as during the preparations, the BVT officers, especially those from the Prevention department, sought the experiences of colleagues in countries like France, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Germany with comparable programs. A key insight is that the target group does not take state organizations - especially security forces like the police - seriously. More precisely: they deeply mistrust them.

"Real Need" for Exit Program

Therefore, a central role in direct contact with potential leavers will also be played by the probation assistance association "Neustart" and the "Extremism Counseling Center". Both associations operate exactly where initial contacts with potential clients are

SPARTANAT is the online magazine for Military News, Tactical Life, Gear & Reviews.

Send us your news: [email protected]

Ad

similar

Get the weekly SPARTANAT newsletter.

Your bonus: the free E-Book from SPARTANAT.