Get the weekly SPARTANAT newsletter.

Your bonus: the free E-Book from SPARTANAT.

MILITARY OBSERVER WESTERN SAHARA: Following the Dust

Carsten Dombrowski, a Military Observer of the German Bundeswehr in West Sahara, shares his experiences. From setting up camp to patrolling, he details the challenges faced in a challenging environment.

15 square meters of privacy

Upon arrival at the military airfield in SMARA, I was taken by vehicle to the adjacent camp, the UN Camp SMARA. Everything was quiet in the midday sun when I arrived, and I first settled into my container. 15 square meters of privacy. Sandy, dusty, equipped with a dripping and humming air conditioner, I began to set up my new home. After about two hours of basic cleaning, I could finally feel some satisfaction.

Always following the dust trail

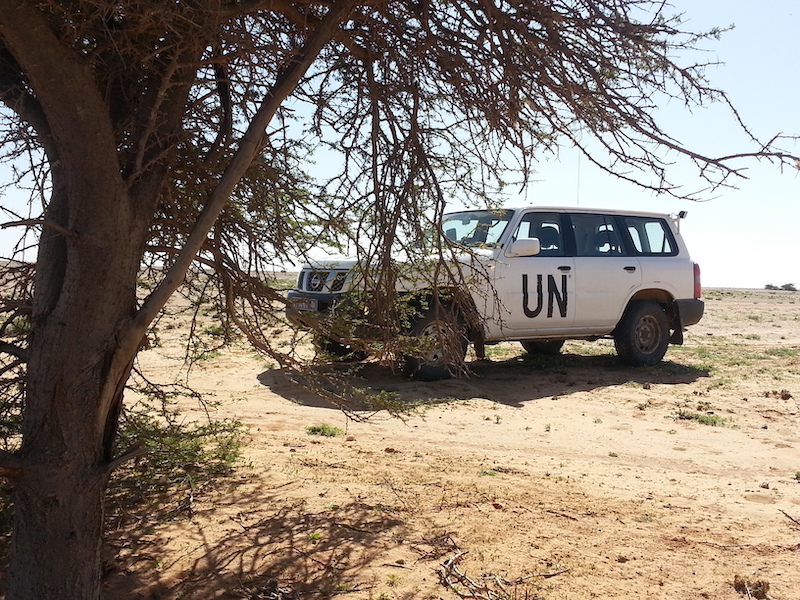

After this initial briefing, I prepared for the first patrol. Orders given, route planned, and individual preparation. Each patrol consists of at least two vehicles, manned by four military observers. For me, as a "Greenhorn," my first role was to drive the second vehicle.

“Following the Dust”. Simply put, I just had to drive, follow the instructions of my co-driver and vehicle commander, and not lose sight of the dust trail of the vehicle in front of me. Sounds simple, but it wasn't. Technical service before departure, meaning checking the technical readiness following a checklist, equipping survival gear, checking radios and navigation devices, took a long time especially at the beginning of the mission. This shortened my already short night by another 1-2 hours. Breakfast was also skipped, as the local bakery delivers fresh bread only after departure. Instant coffee and stale bread leftovers from the day before had to suffice. After a final radio check, we set off on our first drive.

Anyone who imagines that a desert like the Sahara consists exclusively of sand is mistaken. At least the part of the desert where I mainly operated was stony desert with sandy areas. The surface resembled more of a moonscape than the images of sand dunes I had in mind. Accordingly rough, or rather rustic, was the drive. Constant impacts on the vehicle and crew quickly left their marks. Despite significantly reduced speed, around 20 to 30 km/h, the crews quickly became tired and exhausted. Malfunctioning vehicle air conditioners at an outside temperature of about 40 degrees also took their toll. Therefore, it is not surprising that a driving distance of about 80 kilometers takes up the entire day. If something goes wrong, like a flat tire or getting stuck in the mud, then everything takes even longer. A tire change was necessary on every patrol. With some practice, we were able to change it even during a sandstorm in under 10 minutes.

With the setting sun, we reached our camp exhausted to begin the post-mission debrief. Writing reports on what we saw and checked during our journey, technical service on the vehicles, disarming the vehicles, and finally, after a long day, taking a refreshing shower if water was available. However, the water supply was fragile, the sanitary containers were old and dilapidated, and the UN logistics were cumbersome, so very often a 1.5 liter water bottle had to serve as a shower.

After dinner, (cooked) by Moroccan kitchen soldiers, it was quickly time to go to bed to be somewhat rested for the next day. I usually had at least two to three hours of "free time", unless a problem in my additional responsibilities torpedoed this goal. This happened when, for example, travelers from other teamsides took quarters with us, and I had to provide them with bedding and cleaning supplies, or when a toilet broke and I had to arrange for repairs at the distant headquarters since I had no time during the day. After all, I was on the move, and a civilian technical service of the UN does not work in the evenings. So, my email asking for assistance usually went out at night, and I hoped to find a willing and competent contact person somewhere who would send a maintenance team to us. Unfortunately, such processes always took a long time, and we had to wait for a visit to be worthwhile, meaning several things needed to be repaired at once. This always meant living for weeks with significantly reduced infrastructure. In extreme cases, several weeks without a shower and only with local toilets (hole in the ground). Enough complaining.

More reports on mission drives and the training to become a PAPA LIMA, the patrol leader, will follow in the next report.

Military Observer in Western Sahara - Read more:

Part 1: The Selection

Part 2: The Training

Part 3: Helipatrol and False Tanks

Part 4: In the Land of the Puszta and Magyars

Part 5: When German Soldiers Go Traveling

Questions? Contact the CAPSARIUS ACADEMY at our [email protected] with the subject "Morocco".

Those who want to receive the exclusive and automatic Capsarius Academy newsletter must register HERE. CALLSIGN DOC will then arrive by email. Old issues available in the archive.

CAPSARIUS ACADEMY on the internet: www.capsarius-akademie.com

SPARTANAT is the online magazine for Military News, Tactical Life, Gear & Reviews.

Send us your news: [email protected]

Ad

similar

Get the weekly SPARTANAT newsletter.

Your bonus: the free E-Book from SPARTANAT.