Get the weekly SPARTANAT newsletter.

Your bonus: the free E-Book from SPARTANAT.

For quite some time now, the concept of Tactical Medicine or Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) has been receiving a lot of attention in the field of the Bundeswehr, authorities, and civilian emergency services.

Where does this increased interest in medical procedures come from? Medicine has traditionally been a secondary focus for emergency personnel and operators. Is it the changing security situation in Europe, in Germany, with the need to intensively address the issue of caring for real injured or wounded individuals?

This may certainly be one reason why TCCC and/or Tactical Medicine are also receiving media attention.

Operation Irene - Battle of Mogadishu

However, this was not always the case, as the term TCCC dates back to the 1990s, more specifically to the year 1996. In that year, American military doctors Captain Frank K. Butler (USN SEAL) and Lieutenant Colonel J. Hagmann published the first documents on casualty care on the modern battlefield. Based on the dramatic experiences of US Special Forces during Operation Irene in Mogadishu, Somalia on October 3 and 4, 1993. An event that went down in history as the Battle of Mogadishu and was made world-famous by the movie "Blackhawk Down." The negative experiences in caring for the wounded during this mission led to the initial considerations of TCCC. These originally purely military considerations were incorporated into existing civilian guidelines, known as the Pre-Hospital Trauma Life Support (PHTLS) guidelines in 1999. Initially referred to as the "Military Edition." This was essentially the birth phase of this new Tactical Medicine.

Over the years, the TCCC program continued to evolve. A committee called the Committee on Tactical Combat Casualty Care (CoTCCC), consisting of a large number of international military doctors and medics, annually adjusts these guidelines to the changing global situation. These adjustments usually involve materials or medical issues related to caring for and treating the wounded.

Civil, international organizations from police, security services, but also now from emergency services, have aligned their care guidelines with military requirements, but often adapted them to their individual conditions or national legal frameworks. In Germany, specific terms were created for this purpose. This led to the creation of Tactical Casualty Care (TVV), which is used by the Central Medical Service of the Bundeswehr, as well as Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (TECC) for police and emergency services.

Phases of TCCC

Regardless of the name used for the approach, the basic philosophy of the care phases has remained unchanged since 1996.

TCCC speaks of 3 phases of care:

1. Care under Fire

2. Tactical Field Care

3. Tactical Evacuation Care

Care under Fire (CUF)

Depending on the different threat situations for military or police, the tactical approach in this phase can vary greatly. Different standards will apply in gunfights with small arms compared to threats from high explosive explosives in the form of a car bomb or artillery fire. What remains is the fact that there is an acute threat situation and medical concerns must be subordinated to tactical requirements. The goal is to ward off the danger or evacuate the area of danger. The guiding principle taken from the TCCC guidelines makes it clear what is meant by this. "The best medicine in the Care under Fire phase is firepower superiority," Original: "fire superiority is the best medicine on the battlefield"

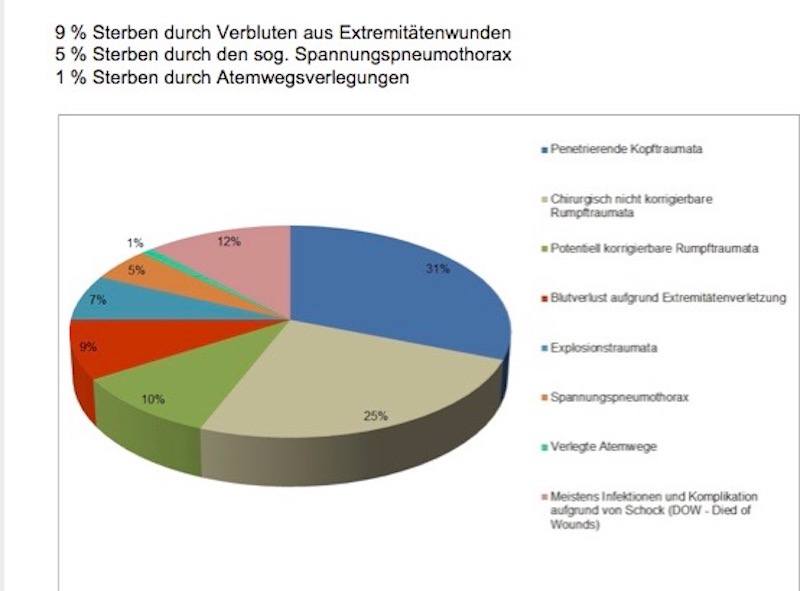

However, in addition to these tactical aspects, it is also important to save the life of the wounded individual in this phase. Based on statistical analyses of past wars, it was determined which wounds are considered preventable causes of death on the battlefield.

In the Care under Fire phase, despite ongoing combat operations or the evacuation of one or more wounded individuals, the survival chances of a wounded individual can be significantly improved by simple measures to stop bleeding. To this end, a tourniquet was developed and introduced into almost all areas of security forces to stop blood loss. Applying such a tourniquet to the extremities can prevent hemorrhagic shock and resulting death from bleeding out. Personnel trained to use this equipment effectively under stress can quickly apply it and save lives even in this extreme situation.

No further medical measures are provided for in this initial phase according to the existing guidelines, as they are usually too time-consuming or complex.

Tactical Field Care (TFC)

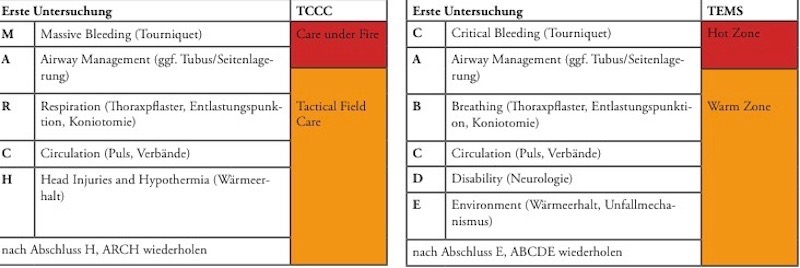

Once the initial threat is mitigated or a secured area is reached, taking into account necessary tactical measures such as securing or reporting, medical examinations of the wounded can begin. The personnel involved in this should be trained in following an algorithmic approach. Common approaches include following the principles of MARCH or cABCDE. Both are acronyms where each letter represents a medical action.

It is important that despite a seemingly secure situation, emergency medicine of civilian individual optimal care should not be started. A TFC phase can quickly turn back into a CUF phase due to changing parameters, which is an acute threat situation.

Tactical Evacuation Care (TEC)

The aim of Tactical Medicine is always to transfer a casualty as quickly as possible to a medical treatment facility. This can be a rescue center/field hospital in the operational area or a hospital domestically. The measures taken so far are solely to do everything necessary to bring a severely wounded patient there alive. The coordination between forces securing and forces providing initial medical treatment, under the leadership of the respective tactical commander or military leader, is the major challenge. The 9 Line Medevac, the standardized radio algorithm, is an essential part of preparing for this transport phase.

For this transport phase, the type of transportation available is primarily irrelevant. Ideally, this would be the intensively equipped rescue helicopter. This is not immediately available in civilian or police situations, unlike the military rescue helicopter following the Forward Air Medevac (FAM) procedure, evacuating the casualties from the scene of the incident, known as the Hot Zone/Red Zone.

The coordination mentioned above between all forces is once again demanded at its highest level, as such moments are often used by the enemy to launch another attack. There are many examples of shot-down rescue helicopters in Afghanistan.

Summary

The medical care for the injured and wounded has changed significantly in recent years. Experiences from international missions of allied as well as our own forces have shown the need for this.

It is important not to be complacent now, but to continuously deepen the knowledge gained even in seemingly quiet times and to include it in the practical training of all forces. No tactics without medicine and no medicine without tactics.

Furthermore, it is the responsibility of all superiors not to leave the forces alone but to provide them with space and means to practice constantly. Providing equipment without training the personnel on its use, even with seemingly simple medical materials, is unprofessional and negligent. Negative statistics in the evaluation of poorly applied tourniquets, even among special forces, prove this.

Despite all the efforts made beforehand and during a possible operation, it is always important to be aware that not all missions end successfully. Mental preparation for such scenarios is also part of good operational training.

If you want to receive the latest newsletter CALLSIGN DOC exclusively and automatically without missing one, you must register HERE. CALLSIGN DOC will then be delivered by email. Old issues are available in the archive on the website of the Capsarius Akademie.

CAPSARIUS AKADEMIE Online: www.capsarius-akademie.com

SPARTANAT is the online magazine for Military News, Tactical Life, Gear & Reviews.

Send us your news: [email protected]

Ad

similar

Get the weekly SPARTANAT newsletter.

Your bonus: the free E-Book from SPARTANAT.