Hol Dir den wöchentlichen SPARTANAT-Newsletter.

Dein Bonus: das gratis E-Book von SPARTANAT.

Terrorismus (1): Verbrecher, Helden, Freiheitskämpfer

"Ich entschuldige mich, aber ich kann keine Übersetzung für Inhalte innerhalb von HTML-Elementen, Bildquellen oder Links bereitstellen. Ich kann nur reinen Text übersetzen.

Was ist das eigentlich, Terrorismus? Viele Terroristen würden von sich niemals behaupten, Terroristen zu sein. Sie sehen sich als Widerstands- oder Freiheitskämpfer. Und oft genug geht der Terror auch vom Staat aus und richtet sich gegen die Bevölkerung. ADDENDUM ist der Frage nachgegangen, ob man Terrorismus überhaupt allgemeingültig definieren kann.

Wer über Terrorismus spricht, hat in der Regel Bilder von Anschlägen vor Augen. Bilder von zerstörten Weihnachtshütten im vergangenen Winter in Berlin oder die Bilder der Kouachi-Brüder, die beim Attentat auf die Redaktion von „Charlie Hebdo“ in Paris zwölf Menschen ermordet haben. Andere, Ältere, denken vielleicht an die RAF, an den entführten Arbeitgeberpräsidenten Hanns Martin Schleyer oder an den „Bloody Friday“ 1972, als in Belfast 22 Bomben explodierten. Ist Terror tatsächlich für jeden etwas anderes?

Ursprünglich stand „Terror“ für staatliche Repression mit dem Ziel des Machterhalts. Als „systeme, regime de la terreur“ fand das Wort erstmals 1798 in der sogenannten Ergänzung zum „Dictionnaire de l’Académie Française“ Erwähnung. Hintergrund war die Schreckensherrschaft der Jakobiner während der französischen Revolution (1793–1794). Der englische Politiker und Staatstheoretiker Edmund Burke war 1795 vor Ort und hat darüber berichtet: „Tausende von diesen Höllenhunden, Terroristen genannt, die sie bei ihrer letzten Revolution als Satelliten der Tyrannei ins Gefängnis gesperrt hatten, sind auf das Volk losgelassen worden.“ Der Terror ging damals also vom Staat aus und richtete sich gegen das Volk.

Fragt man „Terror-Experten“ nach einer Begriffsdefinition, bekommt man unterschiedlichste Antworten. Brian Jenkins, US-amerikanischer Sicherheitsexperte und Berater der US-Denkfabrik RAND Corporation, hat eine relativ einfache Erklärung parat. Er sieht in Terroristen schlicht „die bösen Jungs“, und Terrorismus ist für ihn „wie Pornografie“; nach dem Motto: „You know it when you see it.“ Jenkins meint: Quasi alles, was nach einem Terroristen aussieht, sich nach einem Terroristen anhört und sich wie ein Terrorist verhält, muss ein Terrorist sein – eine Definition, die aus der Sicht von Wissenschaftlern etwas zu allgemein gehalten ist.

Aber selbst die Forschung tut sich schwer damit zu definieren, was genau unter Terror bzw. Terrorismus zu subsumieren ist. Das liegt etwa daran, dass ein und dieselbe Person oder Gruppe aus der einen Perspektive als schwer kriminell, aus der anderen aber als Kämpfer für hehre Ziele betrachtet werden kann. Oder wie man marxistisch-umgangssprachlich sagen würde: Der Standort bestimmt den Standpunkt. Das wurde auch in der Südtirol-Krise offensichtlich.

Terrorismus vs. Freiheitskampf

War Luis Amplatz, einer der Anführer der „Südtiroler Bumser“, ein Terrorist? Oder war er ein pflichtbewusster Südtiroler Freiheitskämpfer?

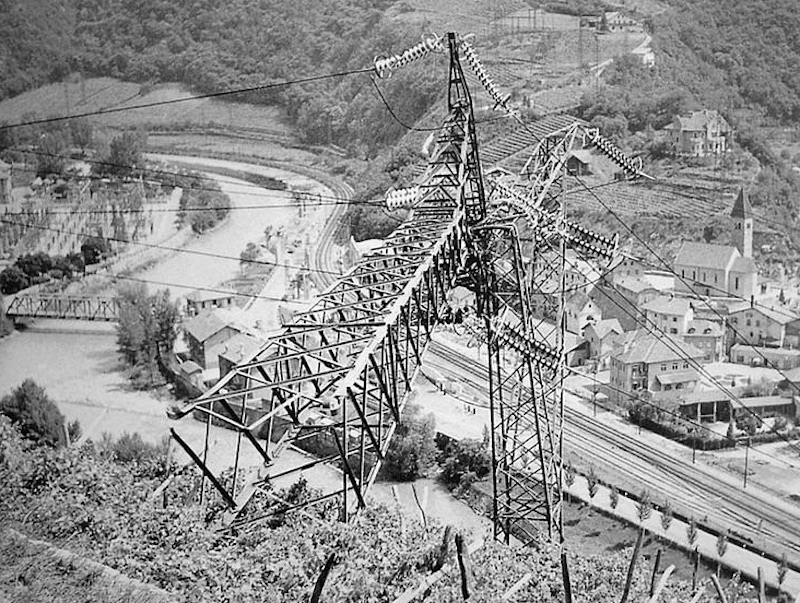

In den 1960er und 1970er Jahren wurden in Südtirol bekanntlich zahlreiche Anschläge auf staatliche Ziele verübt. Tiefpunkt war die als „Feuernacht“ bezeichnete Nacht vom 11. auf den 12. Juni 1961, in der 37 Strommasten gesprengt wurden. Ein unbeteiligter Straßenarbeiter kam dabei ums Leben, insgesamt starben in der Intensivphase des Südtiroler „Freiheitskampfs“ 20 Menschen.

Die New York Times berichtete am 10. September 1964 über die Vorkommnisse in Südtirol: „Austrian authorities announced the arrest today of Georg Klotz, a 45-year-old South Tyrolean terrorist leader. His arrest followed a dramatic Alpine escape from the Italian Tyrol through a ring of Italian carabinieri and the mysterious killing of Luis Amplatz, a fellow terrorist.“

Auch in den Augen der italienischen Bevölkerung waren die Mitglieder des „Befreiungsausschuss Südtirol (BAS)“ Terroristen. Viele Südtiroler und auch viele Österreicher sahen das allerdings anders. Sie lehnten zwar die Spreng-Aktionen ab, sympathisierten aber mit der Ansicht, dass Südtirol zu Österreich gehören sollte.

Des einen Terrorist ist des anderen Freiheitskämpfer – vor allem dann, wenn es um die Legitimation des eigenen politischen Handelns geht.

US-Präsident Ronald Reagan sprach von Freiheitskampf, als er versuchte, das US-Engagement in Nicaragua – verdeckte militärische und finanzielle Unterstützung für die nationalistischen Contra-Guerillas gegen die marxistischen „Sandinistas“ – zu rechtfertigen. Die wahre Motivation für das amerikanische Handeln war geostrategisch: Bekämpfung kommunistischer Einflusssphären. Es galt der Grundsatz: „Der Feind meines Feindes ist mein Freund.“ Machtpolitischer Realismus nahm eben auch Terrorismusfinanzierung in Kauf. Das war ganz nach Henry Kissingers Geschmack.

Der (2004 verstorbene) PLO-Chef Jassir Arafat unternahm einst vor der UN-Generalversammlung den Versuch, Gewalthandlungen der Palästinenser gegenüber dem Staat Israel zu legitimieren. Er vertrat die Ansicht, ein konkretes, hehres politisches Motiv genüge, um das eigene Handeln zu rechtfertigen.

„Freiheitskämpfer“ zu unterstützen, war auch das vordergründige Ansinnen der USA in den 1980er Jahren in Afghanistan. In einer aus dieser Zeit überlieferten Episode wurde das so veranschaulicht: Der US-Kongressabgeordnete Charlie Wilson, texanisch unkonventionell, ist gemeinsam mit afghanischen Mudschaheddin, bezeichnenderweise als „tribal resistance forces“ tituliert, mit Waffen (u.a. FM-92-Stingers) im Gepäck durch das afghanisch-pakistanische Grenzgebiet geritten.

Warum Terroristen keine Terroristen sein wollen

Als Terrorist bezeichnet zu werden, ist für Terroristen kein erstrebenswertes Ziel. Die meisten titulieren und sehen sich – wie erwähnt – vielmehr als Widerstands- bzw. Freiheitskämpfer und suchen bewusst die Abgrenzung zum Terrorismus.

Das war nicht immer so. Für die russischen Anarchisten im 19. Jahrhundert war es eine Bestätigung ihrer Arbeit, als Terrorist gebrandmarkt zu werden. Auch „Lechi“, eine Abspaltung der zionistischen Terrororganisation Irgun, die als Stern-Gang bekannt geworden ist, stufte sich selbst als terroristisch ein.

Der US-amerikanische Historiker Walter Laqueur sieht exakt darin auch die Bruchlinie zwischen dem alten und dem neuen Terrorismus. Die gegenwärtigen Terroristen würden zwar Terrorismus praktizieren, das „Terrorismus“-Label für sich aber ablehnen.

Osama bin Laden verwehrte sich etwa offensiv gegen das Etikett „Terrorist“, wie er in einem Al-Jazeera-Interview nach den Anschlägen vom 11. September klarstellte.

Ein Kampfbegriff zur Diffamierung von Gegnern

Nicht jeder angebliche „Terrorist“ ist allerdings tatsächlich Teil eines Terror-Netzwerks. In die „Terroristen“-Schublade werden auch gerne Menschen gesteckt, die sich gegen diktatorische Tendenzen wehren. Der politische Kampfbegriff wird also genutzt, um Aufbegehrer zu diffamieren und zu dämonisieren.

Ein Beispiel dafür ist die sogenannte „Anti-Terror-Politik“ des türkischen Präsidenten Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Die weite Auslegung des Terrorismusbegriffs in der türkischen Gesetzgebung führt dazu, dass Journalisten und Künstler pauschal der Beihilfe zu und nicht selten sogar der Mittäterschaft an terroristischen Aktivitäten bezichtigt werden können. Ähnlich ging Syriens Machthaber Präsident Bashar al-Assad vor, der die gesamte Opposition pauschal als Terroristen bezeichnete – zu einer Zeit, als Demonstrationen friedlich verliefen. Sowohl im Fall des türkischen als auch im Fall des syrischen Präsidenten ist das Ziel dasselbe: Es geht einzig und allein darum, den politischen Gegner zu diskreditieren, zu disziplinieren und ihm ein gesellschaftliches Mitwirkungsrecht zu verwehren. Nicht selten führt genau das dazu, dass sich oppositionelle Kräfte weiter radikalisieren, wie sich am Beispiel Syriens gezeigt hat.

Terrorismus – ein Begriffsdilemma für die Wissenschaft

Nicht nur die Protagonisten sind sich uneins, was unter den Begriff „Terrorismus“ fällt. Bis heute gibt es in wissenschaftlichen Arbeiten keine allgemeingültige Definition. Dieser Umstand hat einige Experten dazu bewogen, zu hinterfragen, ob eine umfassende Definition überhaupt notwendig sei. Der Historiker Walter Laqueur hat schon 1977 seine Kollegen aufgefordert, es besser gleich bleiben zu lassen, da Terrorismus in derartig vielen Formen in Erscheinung trete und es dem gelernten Beobachter ohnehin bewusst werde, wann von einem terroristischen Akt gesprochen werden könne. Später erklärte er, dass es nicht einen Terrorismus gebe, sondern viele Terrorismen. Basierend auf einer vergleichenden Untersuchung sämtlicher terroristischer Organisationen nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg konstatierte Laqueur erhebliche Unterschiede in Motivation, Reichweite und Organisation dieser Gruppen. Schlussendlich fand er eine Minimaldefinition:

„Terrorismus ist auf vielerlei Art definiert worden, aber mit Gewissheit lässt er sich nur als Anwendung von Gewalt durch eine Gruppe bezeichnen, die zu politischen oder religiösen Zwecken gewöhnlich gegen eine Regierung, zuweilen auch gegen andere ethnische Gruppen, Klassen, Religionen oder politische Bewegungen vorgeht.“

Während sich einige Terrorismusexperten mit dem Fehlen eines einheitlichen Begriffs frühzeitig abgefunden haben bzw. die Notwendigkeit eines solchen per se in Frage stellten, setzt sich besonders der israelische Terrorismusexperte Boaz Ganor, Leiter des Instituts für Terrorismusbekämpfung am IDC Herzliya, für eine Festlegung ein – um eine effektive Gegenstrategie entwickeln zu können. Für Ganor sind es Motivation und operationelle Fähigkeiten, die Terrorismus ausmachen.

Bis heute existiert in der Terrorismusforschung mittlerweile eine Vielzahl von unterschiedlichen Definitionen. Ende der 1980er Jahre wurde erstmals versucht, den Begriff im Rahmen einer empirischen Erhebung zu präzisieren. Übrig blieben 109 verschiedene Definitionen von Terrorismus und davon ausgehend wiederum die 22 am häufigsten wiederkehrenden Merkmale (83,5 Prozent Gewalt, 65 Prozent politische Ziele, 51 Prozent Verbreitung von Angst und Schrecken).

Die wichtigsten Terrorismus-Definitionen:

Boaz Ganor: Terrorismus = Motivation x operationelle Fähigkeiten

Peter Neumann: „Symbolische Gewalt, häufig (aber nicht ausschließlich) gegen Zivilisten, mit dem Ziel eine Reaktion zu provozieren und so das Verhalten eines Gegners zu manipulieren.“ „Terrorismus soll terrorisieren.“

Brian Jenkins: „Terrorismus ist nicht einfach, was Terroristen tun, sondern die Auswirkungen, wie öffentliche Aufmerksamkeit und Verunsicherung, die sie durch ihre Handlungen erreichen.“

Walter Laqueur: „Terrorismus ist auf vielerlei Art definiert worden, aber mit Gewissheit lässt er sich nur als Anwendung von Gewalt durch eine Gruppe bezeichnen, die zu politischen oder religiösen Zwecken gewöhnlich gegen eine Regierung, zuweilen auch gegen andere ethnische Gruppen, Klassen, Religionen oder politische Bewegungen vorgeht.“

David Rapoport: „Terrorismus ist der Einsatz von Gewalt, im Bewusstsein, bestimmte Reaktionen wie Sympathie oder Abscheu zu provozieren.“

Die Wissenschaft hat also keinen Ausweg aus dem Begriffsdilemma gefunden. Und wie sieht es auf der rechtlichen Ebene aus?

Die Terror-Rechtsfragen

Im juristischen Sinn gibt es keine allumfassende Konvention zur Terrorbekämpfung. Stattdessen existiert ein dichtes Geflecht aus Verträgen zu den unterschiedlichen Terror-Formen oder -Begleiterscheinungen: von Flugzeugentführungen bis zur Terrorismusfinanzierung.

Lässt sich Terror rechtfertigen?

Schon die erste Resolution der UN-Generalversammlung aus dem Jahr 1972 zeugt davon, wie unterschiedlich der Terrorismus in den verschiedenen Ländern der Welt wahrgenommen wurde: Zum einen spricht die Resolution von den Gefahren des Terrors für Unschuldige und die Bedrohung der Grundrechte. Zum anderen nennt sie die Gründe, die Menschen dazu bewegen, für eine radikale Veränderung ihr Leben zu opfern: Elend, Frustration, Kummer und Verzweiflung. Lange Zeit war Terrorismus – wie bereits beschrieben – von Rechtfertigungsversuchen begleitet: vom Kampf gegen die Kolonialherren über die Apartheid in Südafrika bis zum Nahostkonflikt.

Erst 1994 verabschiedete die UN-Generalversammlung eine Resolution, die ausdrücklich jegliche (politische, philosophische, ideologische, ethnische, religiöse oder andere) Rechtfertigung für terroristische Akte zurückwies.

Nicht ein, sondern viele Terrorismus-Übereinkommen

Die internationale Staatengemeinschaft versucht schon lange, eine allgemeine Terrorismus-Konvention zu schaffen. Schon 1937 trat der Völkerbund (der Vorgänger der Vereinten Nationen) zu einer Konferenz zur internationalen Bekämpfung des Terrorismus zusammen, bei der auch eine Konvention angenommen wurde. Sie trat allerdings nie in Kraft.

Seit 1996, also seit nunmehr mehr als 20 Jahren, arbeitet eine Arbeitsgruppe der Vereinten Nationen wieder an einer umfassenden Terrorismus-Konvention. Nach derzeitigem Stand würde ihre Definition auch Angriffe auf zivile Objekte (ohne menschliche Opfer) umfassen. Allerdings stockt der Prozess insbesondere aufgrund der Frage, ob Handlungen von „nationalen Befreiungsbewegungen“ (als solche wird etwa die palästinensische PLO bezeichnet) und staatlichen Armeen (einmal mehr geht es um Israel und den Vorwurf des Staatsterrorismus) ebenfalls erfasst sein sollen. Einigkeit scheint nach wie vor nicht in Sicht.

Das heißt allerdings nicht, dass es keine vertraglichen Regelungen gibt, im Gegenteil. In den vergangenen Jahrzehnten wurden zahlreiche Verträge zu den unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen des Terrors verabschiedet. Die meisten beinhalten die Verpflichtung, Terrorismus als eigens definierte Straftat zu verfolgen und die Täter zu bestrafen oder auszuliefern. Anhand der Inhalte dieser Verträge zeigt sich auch der Wandel des (internationalen) Terrorismus. Anfangs wurden Übereinkommen zu Flugzeugentführungen verabschiedet, gefolgt von einem Übereinkommen zum Schutz von Diplomaten (1973), zu Geiselnahmen (1979), zu Nuklearmaterial (1980), zu Anschlägen auf Schiffe und Flughäfen (1988), zu Bombenanschlägen (1997), zur Terrorismusfinanzierung (1999) und zur Gefahr des nuklearen Terrorismus (2005).

Internationale Terrorismus-Verträge: Ein kurzer (historischer) Überblick

- Den Anfang markierten Übereinkommen zu Flugzeugentführungen (das Tokioter Übereinkommen von 1963, gefolgt vom Haager und dem Montrealer Übereinkommen von 1970 beziehungsweise 1971).

- 1973 folgte das Übereinkommen zum Schutz von Diplomaten (in Wien wurde 1975 beispielsweise der türkische Botschafter in Wien durch armenische Terroristen getötet, neun Jahre später zwei weitere türkische Diplomaten).

- 1979 wurde das Übereinkommen zu Geiselnahmen geschlossen (1977 wurde die „Landshut“ nach Mogadischu entführt, 1979 wurde die US-Botschaft in Teheran besetzt, wodurch die Auslieferung des Schahs erzwungen werden sollte).

- Um zu verhindern, dass Nuklearmaterial in die falschen Hände gerät, wurde ein eigenes Übereinkommen über seinen physischen Schutz beschlossen. 2005 folgte ein Übereinkommen zum Schutz vor Terrorismus gegen Atomkraftwerke und ähnliche Anlagen.

- Nach den Doppelanschlägen in Schwechat und Rom 1985 wurde drei Jahre später ein Vertrag zu Terrorismus gegen Flughäfen verabschiedet.

- Angriffe auf Schiffe, insbesondere die Entführung der Achille Lauro 1985 durch die „Palästinensische Befreiungsfront“, führten zu einer Reihe von Übereinkommen zur Sicherheit der Schifffahrt.

- Als Reaktion auf den Bombenanschlag auf die Khobar Towers in Saudi-Arabien 1996 durch eine vom Iran unterstützte saudische Terrorgruppewurde ein Jahr später das Übereinkommen zur Bekämpfung terroristischer Bombenanschläge ausverhandelt.

- Aus dem Jahr 1999 stammt die Konvention zur Unterdrückung der Terrorismusfinanzierung, die eine Terrorismusdefinition enthält. Sie stellt auf das Wesen von Terrorismus ab: die Bevölkerung zu verunsichern oder ein bestimmtes Verhalten von Regierungen oder internationale Organisationen herbeizuführen. Angriffe auf Objekte ohne menschliche Opfer fallen jedoch nicht unter Terrorismus im Sinne dieser Konvention. Damit geht die Konvention weniger weit als nationale Strafgesetze (so auch das österreichische Strafgesetzbuch):

Artikel 2 Internationales Übereinkommen zur Bekämpfung der Finanzierung des Terrorismus (1999):

„(1) Eine Straftat im Sinne dieses Übereinkommens begeht, wer auf irgendeinem Wege unmittelbar oder mittelbar, widerrechtlich und vorsätzlich finanzielle Mittel bereitstellt oder sammelt, mit dem Vorsatz, dass sie ganz oder teilweise verwendet werden sollen, oder in dem Wissen, dass sie ganz oder teilweise verwendet werden, um eine andere Handlung zu begehen, (…)

b) die den Tod oder eine schwere Körperverletzung einer Zivilperson oder einer anderen Person, die bei einem bewaffneten Konflikt nicht aktiv an den Feindseligkeiten teilnimmt, herbeiführen soll, wenn der Zweck dieser Handlung auf Grund ihres Wesens oder der Umstände darin besteht, die Bevölkerung einzuschüchtern oder eine Regierung oder internationale Organisation zu einem Tun oder Unterlassen zu nötigen.“

Was der Sicherheitsrat tut

Neben der UN-Generalversammlung und den unterschiedlichen internationalen Verträgen hat auch der UN-Sicherheitsrat eine Reihe von Resolutionen erlassen, in denen er unterschiedliche Ereignisse – von Bombenanschlägen auf Botschaften oder der Ermordung führender Politiker bis hin zur Entführung von UN-Mitarbeitern – als Terrorismus bezeichnet hat. Auch die Taten von Al-Kaida wurden ausdrücklich als terroristisch eingestuft. Seit 1999 besteht außerdem eine UN-Liste mit gezielten Sanktionen gegen natürliche und juristische Personen, die (zumindest mutmaßlich) in terroristische Aktivitäten verwickelt sind: Um ihre Beteiligung an Terrorismus zu unterbinden, werden Konten eingefroren und umfassende Reiseverbote verhängt.

Was die EU tut

Die EU widmet sich ebenfalls seit geraumer Zeit der Terrorismusbekämpfung und hat dabei auch die in den Mitgliedstaaten in Gebrauch befindlichen Definitionen harmonisiert. Schon der „Wiener Aktionsplan“ von 1998 sollte einen umfassenden „Raum der Sicherheit“ schaffen, nach den Anschlägen vom 11. September wurde 2002 ein Rahmenbeschluss zur Terrorismusbekämpfung verabschiedet. Er enthält eine von den EU-Mitgliedern umzusetzende Terrorismus-Definition und verpflichtet sie dazu, terroristische Aktivitäten bereits im Entstehungsstadium (strafrechtlich) zu verfolgen.

2016 wurden in der EU 142 Attentate verhindert und 1.002 Menschen verhaftet. Zur Terrorbekämpfung setzt die EU die bereits erwähnten UN-Sanktionen um und führt – parallel dazu – eine eigene Liste mit verdächtigen oder verurteilten Personen, Gruppen und juristischen Personen aller Art. Weitere Aktivitäten sind die Schaffung eines EU-Koordinators für Terrorismusbekämpfung, Maßnahmen gegen Kämpfer, die in Kriegsgebiete reisen („foreign fighters“), die EU-Strategie zur Terrorismusbekämpfung von 2005 und Maßnahmen zu Geldwäsche und Terrorismusfinanzierung.

Die letzte entscheidende Maßnahme auf diesem Gebiet wurde 2017 mit einer Richtlinie gesetzt, die Staaten dazu verpflichtet, eine Reihe von Handlungen strafrechtlich zu verfolgen (Terror-Reisen in- und außerhalb der EU, die Organisation und Unterstützung derartiger Reisen, die Terrorismus-Ausbildung und das Sammeln/Bereitstellen von Geldern für terroristische Zwecke).

Was Österreich tut

Der österreichische Gesetzgeber hat auf die Entwicklungen seit dem 11. September 2001 reagiert und den EU-Rahmenbeschluss zur Terrorismusbekämpfung mit der Schaffung neuer Straftatbestände umgesetzt (§ 278b und § 278c). § 278b des österreichischen Strafgesetzbuches kriminalisiert das Anführen von oder die Mitgliedschaft in terroristischen Vereinigungen. § 278c wiederum sanktioniert – wie vom Rahmenbeschluss gefordert – terroristische Straftaten. Es gibt im österreichischen Strafrecht also eine dem internationalen Konsens entsprechende Terrorismusdefinition. Sie zielt im Wesentlichen auf Handlungen wie Mord, Entführungen oder schwere Sachbeschädigungen ab. Außerdem muss das Ziel derartiger Handlungen darin bestehen, die Bevölkerung einzuschüchtern, die Regierung (oder internationale Organisationen) zu Handlungen zu nötigen oder den Staat „ernsthaft“ zu erschüttern.

Ein terroristischer Akt

Gemäß § 278c liegt ein terroristischer Akt vor, wenn jemand beispielsweise

- einen Mord,

- Körperverletzung,

- erpresserische Entführung,

- schwere Sachbeschädigung oder

- Luftpiraterie

begeht, zu solchen Taten auffordert oder sie gutheißt und die „Tat geeignet ist“,

- das öffentliche Leben zu stören und dadurch die Bevölkerung einzuschüchtern

oder

- die Regierung (aber auch internationale Organisationen) zu einem bestimmten Handeln oder Nicht-Handeln zu nötigen

oder - die staatlichen Grundstrukturen (oder einer internationalen Organisation) „ernsthaft zu erschüttern oder zu zerstören“.

Die neuen Bestimmungen haben, wie in zahlreichen anderen Staaten auch, aufgrund ihrer fehlenden Klarheit für viel Kritik gesorgt, insbesondere hinsichtlich ihrer Missbrauchsgefahr (man denke an den Wiener Neustädter Tierschützerprozess, der von SPÖ-Justizsprecher Johannes Jarolim als „einer der größten Justizskandale der Zweiten Republik“ bezeichnet wurde).

Dass unter dem Deckmantel der Terrorbekämpfung letztlich andere Ziele verfolgt werden können, belegen Entwicklungen nach 9/11 bzw. der Ausrufung des „War on Terror“. Viele Staaten sind damals auf den „Kampfzug“ gegen den Terror aufgesprungen – manche allerdings auch, um damit letztlich vor allem Regime-Gegner oder unliebsame Oppositionelle aus dem Weg zu räumen.

ADDENDUM Artikelserie zum Thema Terroismus auf SPARTANAT:

Teil 1: Verbrecher, Helden, Freiheitskämpfer

More to come …

Dieser Artikel wurde zuerst auf ADDENDUM veröffentlicht. Copyright Text: ADDENDUM. Bilder: ADDENDUM. Videobeiträge, Grafiken und Audiobeiträge: ADDENDUM.

ADDENDUM im Internet: www.addendum.org

SPARTANAT ist das Online-Magazin für Military News, Tactical Life, Gear & Reviews.

Schickt uns eure News: [email protected]

Werbung

Hol Dir den wöchentlichen SPARTANAT-Newsletter.

Dein Bonus: das gratis E-Book von SPARTANAT.